Diversify Your Lawn

Traditional lawns are typically kept pristine through frequent mowing, irrigation, and applications of fertilizers and pesticides. These are harmful practices that pollute our air and water, deplete our soil of nutrients and the microbes that maintain its structure, and consume valuable and possibly scarce resources – all while providing nothing to feed butterflies, bees, birds, and other animals. Nevertheless, lawns are generally the default landscape in many cities and suburbs.

Do we really need so much lawn? If each of us were to shrink our lawn in half, (see Tallamy, Douglas W. Nature’s Best Hope. 2019) a significant portion could be transformed into valuable wildlife habitat that engages us in observation and discovery throughout the year. While still keeping some lawn to serve as pathways through the landscape or outdoor rooms for gathering and recreation, imagine the profound impact on our environmental and psychological well-being if North America’s millions of acres of lawn were reduced by half!

Transform Your Lawn

For the lawn that you decide to keep, transforming it by diversifying its plant composition is a cost effective, relatively low effort, and rewarding way to start the process of supporting more life in your landscape. This means allowing your lawn to enrich itself with plants that come in on their own, and supplementing with additional beneficial native species.

Let Your Lawn Flower

To diversify your lawn, the first step is to stop applying chemical pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers, and stop watering. This will save money, energy, water, and time, and eliminate toxins and pollutants from your property.

Next, choose an area to stop mowing for at least one growing season. Keep a mown edge aroudn the perimeter as a demonstration of intentionality and care to your neighbors.

As various species get taller and go to flower, it is the optimal time to identify them, decide what stays and what goes, and appreciate the beauty of lawn “weeds”. Remember, weeds are in the eye of the beholder!

I live in New England, and my go-to references for identification are Newcomb ‘s Wildflower Guide, Wildflowers of New England, and the Native Plant Trust’s online key Go Botany (https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org). I also use the iNaturalist phone app (inaturalist.org), which covers the world.

If you haven’t been using herbicides, you’ll probably discover that mostly innocuous non-native plants dominate the unmown lawn, at least at first. These opportunistic plants grow well in disturbed or depleted soils and can be agricultural weeds.

Species in this group include European grasses, cinquefoils, plantains, dandelions, hawkweeds, clovers, and many more. There is no need to go to great lengths to eradicate them from a lawn, as these species often provide pollinators with nectar and pollen, are medicinal or edible, and improve soil structure and composition with their deep roots or nitrogen-fixing abilities.

Some species are potential butterfly caterpillar food. For example, many sulphurs use clover, and Baltimore Checkerspots and Common Buckeyes may use plantains.

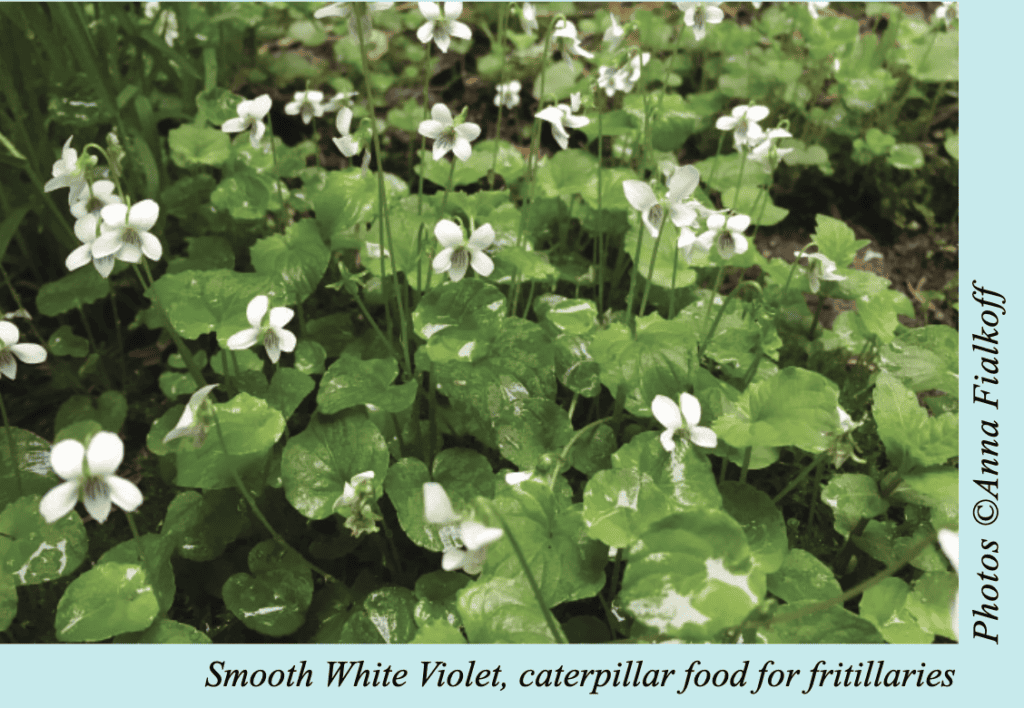

Some lawns may already be filled with a delightful mix of violets as well as native Virginia Strawberry and bluets, all plants that tolerate light foot traffic and mowing.

Let the desired plants set seed and reproduce, and discourage the unwanted plants by cutting them back before they go to seed. Fight the urge to pull unwanted plants since this will bring more weed seeds to the soil surface to germinate.

Before adding new plants, you will need to remove invasive species that are aggressive spreaders, including Ground Ivy, Rampion or creeping bellflower, and Canada Thistle. Smothering with newspaper, plastic, or landscape fabric; digging them up; and persistent mowing are some mechanical ways to remove plants l;ike these. To learn more about invasive plants in New England, visit the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England (IPANE) website: https://www.eddmaps.org/ipane.

Add valuable native plants!

Many native plants support biodiversity as pollinator magnets as well as by providing other food for insects throughout their life cycle. Native in the Aster Family, especially goldenrods, support hundreds of species of bees, moths, butterflies, and other insects. Some plants are essential for specialized insects, like American Lady, whose caterpillars consume leaves of various pussytoes, Pearly Everlasting, and related species. Pussytoes make a lovely ground hugger for well-drained soils in sunny spots.

If you hop eto maintain a lawn-like look, incorporate narrow-leaved plants that grow low and blend well with grasses, such as Strict Blue-eyed Grass, Common Goldstar (Yellow Star Grass) and Bluebell Bellflower (Harebell). These inconspicuous plants may go unnoticed until they begin to bloom in yellows, blues, and soft lavenders that float just above the ground in the mass of grasses and sedges.

Directly sowing seeds into prepared soil can be a successful way to cover the ground with fast-growing plants like Canada Wildrye, asters, coneflowers or Patridge Pea. However, under heavy competition from lawn weeds, most average to slow-growing native plants establish best when planted into bare spots as young seedlings or landscape plugs.

Native plants tolerant of drought, poor soils, and occasional mowing and trampling are well suited for the average suburban lawns, which often sits on construction fill soil or sandy leach fields. I get inspired by inspecting what grows in cemeteries, power line cuts, highway margins, roadsides, and old hay fields, where natural or human-made disturbance keeps the land clear trees and shrubs so lower-growing plants can persist. Purple Lovegrass, Gray Goldenrod, Sundial Lupine, Birdfoot Violet, Butterfly Milkweed, and Flawleaf Whitetop Aster do well in these conditiosn, although on your own property you may prefer not to mow or walk on them.

For shadier settings, consider forests for inspiration: Canada Mayflower, Pennsylvania Sedge, Starflower, and Partridgeberry form a matrix throughout woodland understories in New England, and this combination could be replicated in a shady backyard.

Raise your mower height and reduce the frequency of mowing to once a month or less. Your imagination can run wild with the possibility of what can be encouraged and planted when you let the mower rest. Diversifying your lawn can help you cultivate the skills of observation, patience, and the joy of discovery, while you create a better-suited environment for other living beings to coexist.

Consider making more active strides toward transforming half your lawn footprint into a diverse patchwork of lawn alternatives and groundcovers, meadow or prairie grasses and wildflowers, or native trees, shrubs, and ground-layer plants. All of these can provide maximal native plant biomass for butterflies, birds, and other wildlife to find cover, forage, shelter, and egg-laying habitat.

Editor’s Note

For information on invasive plants in other parts of the United States visit https://www.invasiveplantatlas.org/index.cfm.

Canada offers a free invasive plants field guide, https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/acia-cfia/A104-97-2017-eng.pdf.

As Wild Seed Project’s (wildseedproject.net) program manager, Anna Fialkoff loves sharing her passion for native plants through writing and teaching. She was most recently senior horticulturist for Native Plant Trust (www.nativeplanttrust.org) and holds a BA in Human Ecology fromCollege of the Atlantic and an MS in Ecological Design from The Conway School.