Native Plants, Soil, and Soil Amendments

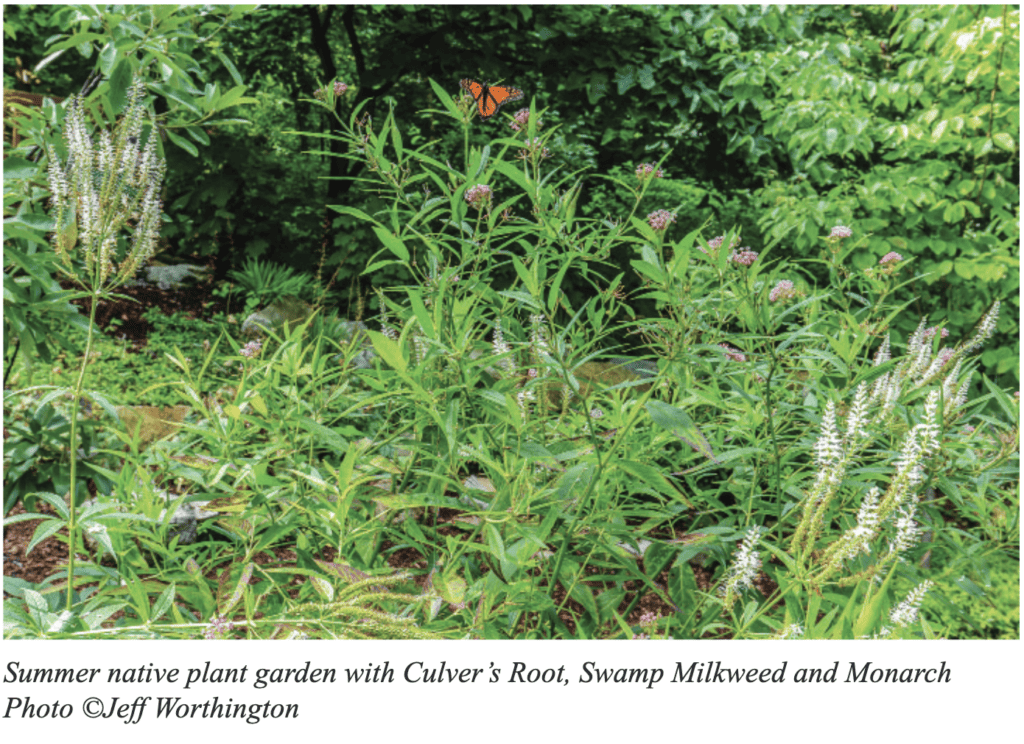

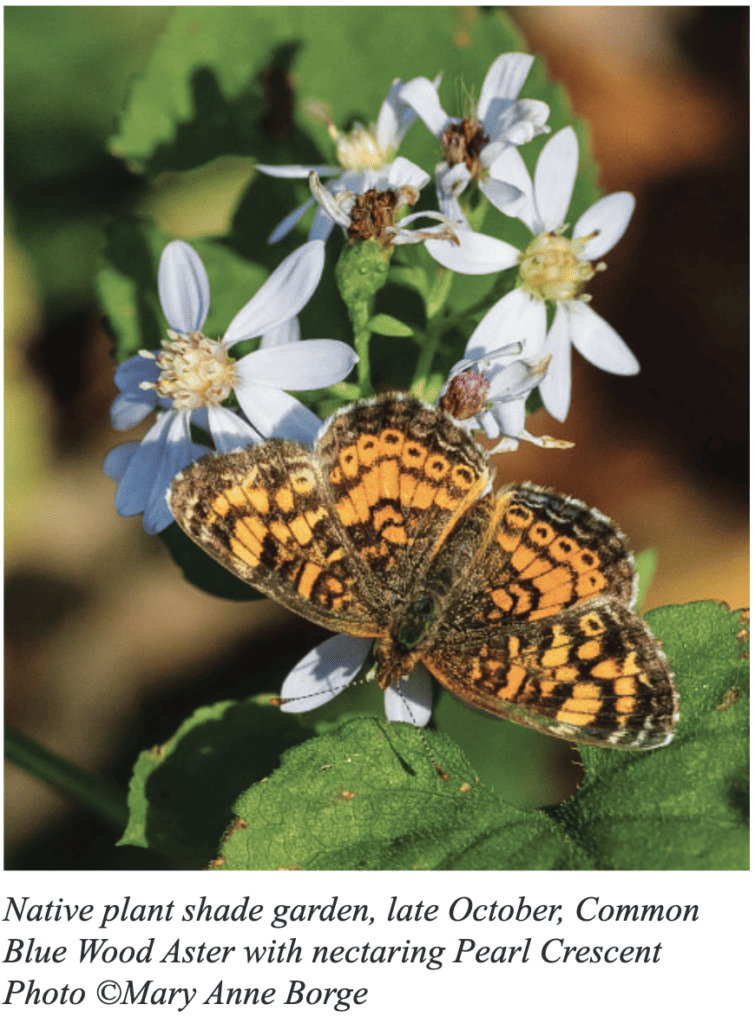

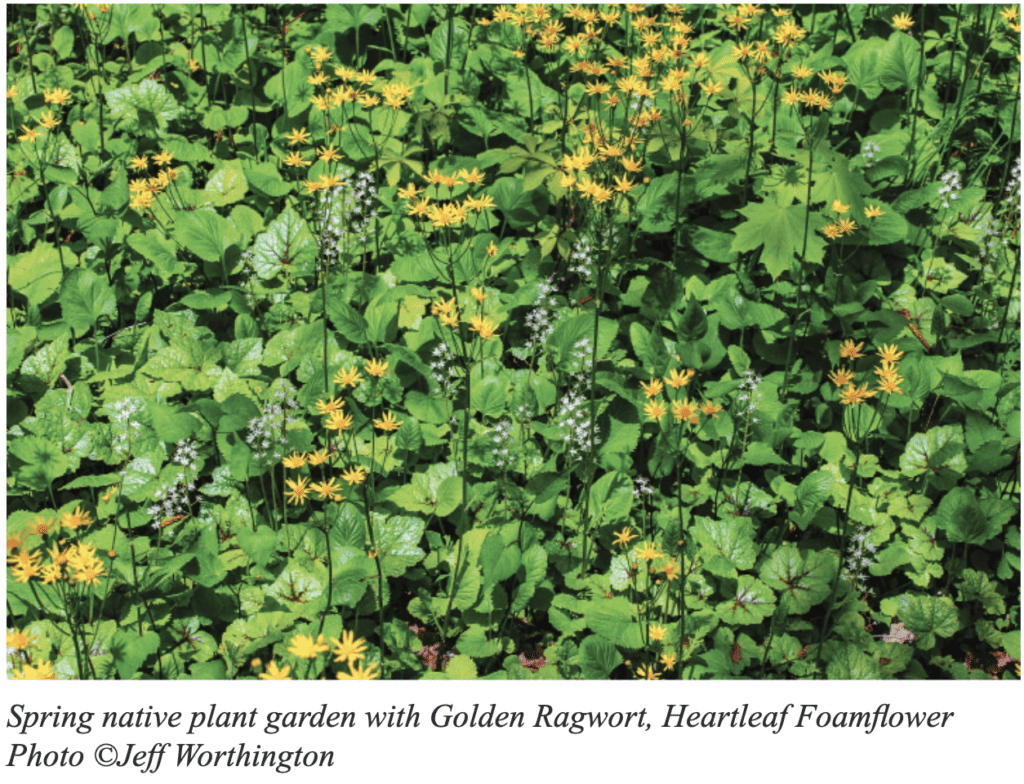

They are adapted to our soils and weather. They need less maintenance, watering, and fertilizer. They support the butterflies, moths, bees, beetles, birds, and other animals that have evolved to depend on them for their very existence. In the many programs have presented over the years, these are just a few of the reasons I have discussed for landscaping with native plants.

So what are the real basics of gardening with native plants?

In establishing a new garden, or enhancing your existing garden, it is always a good idea to work with the conditions you have, since doing so enables you to choose plants that will be more likely to thrive. It’s the “right plant, right place” advice that you may have heard. Conditions to consider include the amount of sunlight or shade you have, and how moist the soil is.

It also helps to understand the type of soil you have – not so that you can amend it, but rather to help you choose plants that will do well for you without requiring a lot of alterations to your environment. Every state has Agricultural Extension offices that will run soil tests for you. The big-box stores sell do-it-yourself soil-test kits, but the results of these are often influenced by your water pH, which can skew the results. The professional labs used by the extension services account for this, so it pays to have them do the work. Test results will include soil pH (level of acidity), levels of nutrients that are important to plant health (phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, calcium, etc.), and soil texture-how sandy, loamy, or clayey is it? The soil texture is an indicator of how quickly or slowly your soil will drain.

The good news is that no matter your garden conditions, rest assured that you will be able to find a suite of native plants that will thrive there. Clay soil is not “poorly drained” it is slow draining, which means you need to find plants that will thrive with their feet wet. Sandy soils tend to drain quickly and be nutrient poor. That is not a bad thing – rather, it is perfect for plants that are adapted to those conditions. Give those same plants too many nutrients (or too much water), and they will languish and die.

Your state or provincial native plant society can help you with information about the plants that will work well for you. Another great way to get ideals for plants that will flourish in your garden and to learn more about them is to take a wander through your region’s natural areas, whether wetland, woodland, desert, or prairie. Take note of the species you see, and the conditions in which they grow and thrive.

You’ve assessed your growing conditions, and know your soil’s attributes. You’ve selected the plants that you think will do well. You’re ready to begin planting. What soil amendments do you need? None! You can plant directly into your existing soil, which is already the best medium for the plants you’ve chosen.

Optionally, you may want to add a thin layer of leaf compost before planting. This will help deter weeds until your plants get established, and give them a little boost of the type of nutrients that keep them healthy,.

When gardening with native plants adapted to your garden’s conditions, do you need to add fertilizer or other soil amendments over time? No. Adding fertilizer may have a negative effect on your plants, making them leggy and weak.

Should you mulch each spring?

While you were exploring local natural areas, you may have noticed that Mother Nature doesn’t pile mulches of shredded wood around the plants, nor does anyone come out and apply other soil amendments. How are the nutrients that plants need replenished in the soil over time? It is the naturally fallen leaves and other plant material that decomposes on the ground that return nutrients to the soil each year. This material also helps to absorb and slowly release rainwater. If you adopt the practice of leaving this natural mulch in your beds, it will eliminate the need to rake, shred, or blow it away in the fall, and to buy and spread mulch in the spring. Nature will replenish the nutrients in your soil each year, all at no cost or effort on your part. This practice is also directly beneficial to many butterflies, moths, bees, and other insects and invertebrates that spend the winter in or under those fallen leaves.

If we choose to grow plants that are not adapted to our garden’s conditions, we will likely have to amend the soil to accommodate them. This is typically not a one-time effort, but rather something that will need to be repeated periodically.

If we use plants that depend on nutrients or conditions that are not naturally found in our gardens, those nutrients will eventually be depleted by the plants, and the growing conditions will degrade. As a result, you must test and amend the soil to keep those plants healthy – potentially an expensive and time-consuming process. Think of a lawn as an example. Lawns that consist of cool-season turf grasses are not well-adapted to growing conditions in many places in North America. Depending on the standards we have for their appearance, lawns may require frequent inputs of water, fertilizer, weed killers, and soil amendments such as lime. Aeration may be required to mitigate compaction. Excess fertilizer can wash into surface waters, degrading water quality. Many of you may live in areas where for reasons of water conservation and water quality, your state, municipality, or water authority discourages lawns and encourages their replacement with native plants – especially if you live in a drought-prone or desert region.

If you garden with the native plants that have adapted to your local soils and growing conditions, it is more cost effective for you, and better for your local ecology and the planet in general, rather than trying to change – through many expensive inputs repeated over time – the natural soil conditions that have taken so long to develop. Iguarantee that with native plants you will still be able to fill your garden with season-long color and diversity that reflects your unique local ecology and supports butterflies, bees, and other wildlife in all their life stages.

Kathleen V. Salisbury is the owner of Katsura Horticultural, a Horticulture Consulting and Education Company. She is also the Director of the Ambler Arboretum of Temple University and an adjunct professor in the Landscape Architecture and Horticulture Department. Her passion for native plants stretches back to her time growing up in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. While a New Jersey resident Kathy served as the president of the Native Plant Society of New Jersey for nine years.